For nearly a century the Chew family ran, at a high profit, an asylum, the building of which still stands at Billington, near Whalley, Lancashire [now the site of the Mytton Hall Hotel and Golf Club]. Its fame was widespread. The Senhouse family of Netherhall in Cumberland paid regularly to Dr. Chew from 1759 to 1774 in order to keep an insane member out of the way. The bills survive among the family muniments. ‘The Centinel’, writing in the Lonsdale Magazine in 1821, burlesqued Dr. Chew, junior (possibly Abraham II, who had actually died in 1819, or his brother James) as follows:

‘I pulled off my uniform and dressed myself in a suit of black, with a great top-coat, a pair of boots, and a gilt-headed cane. Thus accoutred, I sailed out into the country by the name of Dr. Chew, junior. I professed to cure every species of insanity with east and certainty’.

From the de Trafford collection [DDTR] a bundle of papers has recently come to light which provides a fairly detailed account of the origins of this enterprise. In harrowing detail, the Lord Chancellor’s order relating to the custody of an alleged lunatic gives us the melodramatic story.

“Friday the 22nd day of Dec. 1750 in the matter of Richard Stanley, Esq., a lunatick….that…Richard Stanley was the said Thomas Stanley’s only son who was very fond of him & humoured him much in his infancy & when he attained the age of about 20 years Thomas Stanley, his father, thinking him wild and extravagant, used him with great severity. And the said Thomas Stanley & his family then living with Thomas Culcheth Esq., since deceased, on whom the said Thomas Stanley had a great dependence & the said Richard Stanley his son being very passionate and having a very great respect for one of Mr. Culcheth’s maid-servants occasioned great different between them & the said Thomas Stanley being cautious of disobliging Mr. Culcheth & to prevent his son from marrying the said servant-maid, got him confined under the care & management of one James Chew….”

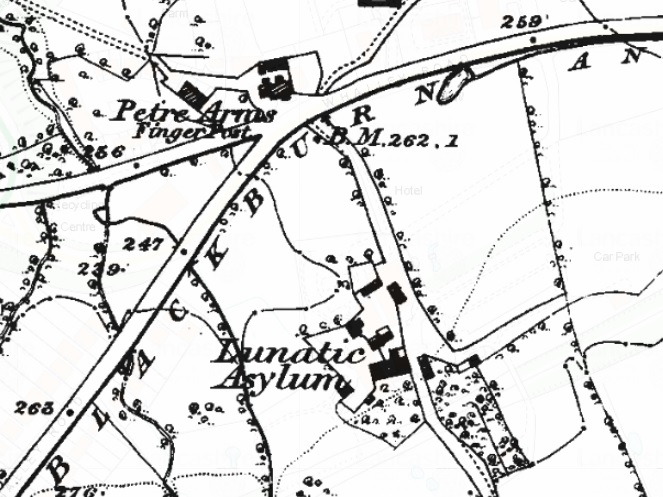

The order goes on to state that Mr. Thomas Culcheth had made a will which provided, among other things, that his manor of Culcheth was to go to Meliora, sister of Richard, after Richard’s death, if he left no heirs. Meliora was married to William Dicconson of Wrightington. She petitioned for a commission of lunacy against her brother, and “by the management and contrivance of Mr. John Chadwick (Steward to the Dicconson family) & the said Mr. James Chew who some time since was a seafaring man…commonly called Dr. Chew who takes care of person (sic) afflicted with lunacy, that the jury found the said Richard Stanley a lunatic and that he enjoyed no lucid intervals so that he was not sufficient to govern himself, his manors etc. And that he had been in a state of furious madness for 4 years then last past & upwards”. The insane had not been examined, however, by any of the commissioners or jury nor had anyone been called as witness by the commissioners except ‘the said James Chew, Thomas Chew who looks after the said James Chews horses & – Lancaster the said James Chew’s barber’. Meanwhile the astute Chadwick was appointed ‘Committee of the said Richard Stanley’s person’ and sister Meliora ‘Committee of his estate’, both by no means honorary appointments. The the description follows of Richard’s treatment – ‘confined in chains in a damp room paved with flagstones in a small outbuilding thatched near to the said James Chew’s dwelling house at Billington…with very indifferent furniture in it’. No regular physician visited him, nor were his friends able in practice to see him.

The petitioners contended that Richard was in fact ‘master of his reason & understanding & capable of conducting himself and his affairs’ on the testimony of those (presumably not friends)’) who had seen him. They moreover suggested that he should be removed from the care of James Chew to his own house at Culcheth ‘with proper persons to attend him which is a pleasant retired place and an air he was formerly used to’. This they believed would be ‘for the recovery of his health’. Proper, qualified physicians should report on him to the Chancellor. If Richard appeared sane, he was of course to be ‘set at liberty’. But if still mentally ill ‘that the present Comittee of his person might be discharged and another appointed’. Affidavits sworn by several well-known local medical men were forwarded to the Chancellor, but his opinion was that Richard should be brought up to London to be examined by the eminent Dr. Monroe, physician to Bethlehem Hospital. He would pronounce whether the disease was curable or not, and, if curable how it should be treated.

The lucrative profession of ‘mad-doctor’ with the perquisite of the Asylum passed like an hereditary office from father to son. The original James Chew died in 1768, to be succeeded by his son, Abraham I, on whose death in 1800, his son, Abraham, took over the practice.

In the Hawkshead-Talbot collection [DDHK] three letters survive from Abraham II to Thomas Hawkshead, relating to his daughter. In his letter 24 Jun. 1812, he offered immediate accommodation at Billington, provided that a certificate under hand and seal of a qualified physician or a surgeon was forthcoming. These were required by Act of Parliament. He suggested a gambit by which Miss Hawkshead might painlessly be allured into his establishment, namely that some of her friends should come with her ‘through this town (Blackburn) under the idea of her going to Scarbro’. He would surreptitiously join them and conduct them to Billington, thus ‘stealing her quietly away’. Clearly chains were not general then, since in April, 1814, she escaped and Dr. Chew explained that she was not so deranged as to be kept under strict confinement. Before Miss Hawkshead died in 1842 she was still ‘Irritable and restless’. She had obviously received no effective treatment. Up to 1834 the cost of maintaining her was £27.60 a half year. In 1834, after Jane Hesmondhaigh, sister of Abraham Chew II, sold the asylum to one Philip Kershaw, a respectable medical gentleman’, the fees doubled.

Abram, in his History of Blackburn, covers the whole ancient parish in much detail, but reveals little knowledge of an institution which some at least of his contemporaries must have remembered. It is to be hoped that from other Northern family collections more facts will emerge to clarify this shadowy corner of the twilight world of early psychiatry.

Notes: The text of this article first appeared in the annual report of Lancashire Record Office, 1973, apart from the additional information in square brackets. Letters relating to the sister of Ingham Walton of Barrowford and her stay at the asylum in the 1840s – known then as Billington Retreat – can be found in DDSP/79/3/1/11

The parody in the Centinel concerns James Chew(b.1771), who was a graduate of Edinburgh University Medical School. One of the references in the Senhouse letters is to Abraham Chew’s financial problems due to the turbulences of the market and his support of his son, James, at Uni. James later graduated having written his dissertation “De Animi Affectionibus” . He became a medic and and after his father’s death took over the running of the asylum at the beginning of the 19th century. You can see this in the land tax records and the payments in the quarterly sessions of Preston to register the asylum for the required number of patients. His brother, Abraham, seems to have been a well-respected member of Blackburn society until his death in 1819.A bust along with eulogy existed/still exists? in St Mary the Virgin’s church in Blackburn.

During James’ period of management there seems to have been accusations of overcrowding and insanitary conditions. One of the annual reports “Visitations” criticises Chew’s Asylum for lack of “airing fields” for the inmates and the non-separation of sexes vis-a-vis toilet facilities. It seems that the older Abraham had in his will envisaged a sharing of the responsibility for the upkeep of the asylum and so when James left to take up a practice in Preston, his brother Abraham and sister Jane took over the management.

James seems to have made few friends in Preston as he was made Physician of the newly opened Preston Dispensary although he was relatively new in the town.The local surgeons and physicians were not amused!

He soon resigned and probably gave his reputation no boost when he fathered a son to Isabel Jackson outside marriage. He did, however, support his son and his son’s mother, as can be seen in his will. He returned to the Blackburn area after the death of his brother Abraham in 1819 to take over the practice (shop). He died a few years later but , unlike his brother, and despite his “nearness” to famous physicians such as John Hull,Alexander Monro, Andrew Munro and James Gregory, never was able to enjoy the warmth and respect of his brother, Abraham.

Paul Sutcliffe

Bochum

Germany

LikeLike

That’s fascinating Paul. Thanks for the additional information.

LikeLike

For more background and detail to the institution you could try my various articles written for “The Lancashire Family History and Heraldry Society”.

VOL.30 Nov 2008 No.4 “Madhouse Farm at Billington-Langho”

VOL 34 May 2012 No.2 “Preston’s significance for the development of Billington Asylum”

VOL 36 Feb 2014 No.1 “Patients who lived and died in Billington Asylum”

VOL 36 May 2014 No.2 “The Chews influence in Blackburn society”

VOL 38 Nov 2016 NO.4 “Richard Hardy: Surgeon of Whalley”

LRO should also have a summary of the documents relating to Billington Asylum, which I sent them. This,although not complete, includes outlines of the content and form of references I had found pertaining to the Asylum pre c. 2009.

Paul Sutcliffe

LikeLike